More than 240 international galleries are participating in Art Basel this year, as it returns to full scale for the first time since before the pandemic. A related Art Week event, Art Central, features almost 100 galleries from Hong Kong and around the world.

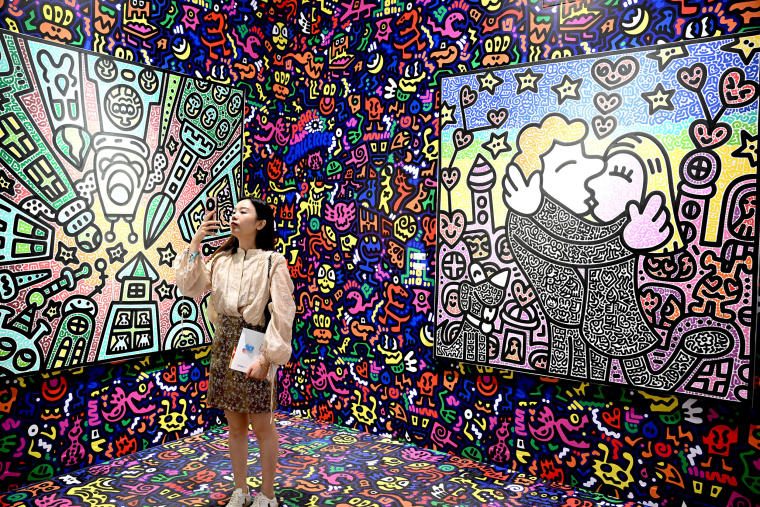

The two events have been thronged with people this week, both serious art buyers as well as casual ticketholders snapping photos and selfies.

The government provided Art Basel with 15 million Hong Kong dollars ($1.9 million) from a fund aimed at promoting major arts and cultural events, which supported Art Central as well. Officials see such “mega events” as a way to revive Hong Kong’s economy and its international reputation, which has been battered by years of pandemic isolation and the crackdown on dissent.

Hong Kong Culture Secretary Kevin Yeung told lawmakers on Wednesday that the government was “committed to promoting Hong Kong as an East-meets-West center for international cultural exchange,” citing the city’s low tax rate and strategic location in Asia.

Art Basel has played down concerns about free expression.

“We have never faced any censorship issues at our shows, nor have we been asked to do anything differently since the introduction of the National Security Law,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “As with all Art Basel shows, our Selection Committee is responsible for reviewing applications and selects galleries solely based on the quality of their booth proposal.”

But that obscures the self-censorship that galleries may now feel is necessary to be included in major art fairs, said Wear, who published a statement last year urging the international artistic community not to participate in Art Basel’s Hong Kong event.

“They don’t have to do it because everybody does it for them,” he said.

Crack-down on dissent bumps up against Hong Kong’s cultural ambitions

The Hong Kong government has been investing heavily in the city as a cultural hub, opening the M+ art museum in 2021 and the Hong Kong Palace Museum in 2022. And the world’s biggest auction houses continue to express confidence: Phillips opened its new Asia headquarters in Hong Kong in 2023, to be followed by Christie’s and Sotheby’s later this year.

But Hong Kong’s cultural development has coincided with a crackdown on dissent in the name of national security, raising difficult questions for international art companies that don’t want to miss out on commercial opportunities.

“They know they have a problem, but they don’t want to talk about it,” said Danish sculptor Jens Galschiot. “Because the moment they talk about it, then they must face it.”

In 2021, a sculpture by Galschiot memorializing the victims of the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in Beijing was dismantled and removed from the University of Hong Kong, where it had stood since 1998. University officials said they removed the sculpture, called the “Pillar of Shame,” “based on external legal advice and risk assessment.”

Hong Kong officials have made it no secret that art could be targeted. The city’s security chief, Chris Tang, said in a letter to Galschiot last year that those seeking to endanger national security could use “artistic creations” as a pretext.

Alexandra Yung, a local artist, art collector and art consultant, said there was a feeling of “apprehension” among Hong Kong’s artistic community, some members of which have moved abroad. Artists now have to be “a bit more aware and more responsible,” she said, amid uncertainty over where the “red lines” are drawn.

While in past years Hong Kong’s Art Week events have featured art related to local politics, Yung said this year she “didn’t see anything that was political at all.”

“I think galleries are more aware of what they would show and what they wouldn’t show,” she said.

Hong Kong was required to pass the Article 23 law under its mini-constitution, known as the Basic Law, but a previous attempt was aborted in 2003 when an estimated 500,000 of Hong Kong’s 7.5 million people took to the streets in protest. Since the national security law was imposed in 2020, however, Hong Kong’s pro-democracy opposition has been all but wiped out, and this time the bill sailed through the legislature, where it passed unanimously on March 19.

The law has been criticized by the United States and others, with Secretary of State Antony Blinken saying it “threatens to further undermine the rights and freedoms of people in Hong Kong.”

The Hong Kong government condemned Blinken’s remarks as “misleading and erroneous,” saying the law is precisely targeted, its crimes and penalties are clearly defined and established freedoms will be protected.

Among the aspects of the new local law of greatest concern to artists is sedition, a British colonial-era crime that Hong Kong officials have resurrected in recent years, said Eric Yan-ho Lai, a research fellow at the Georgetown Center for Asian Law.

The new law expands the crime of sedition, defined as inciting hatred or disaffection toward the Chinese and Hong Kong governments, and raises the maximum punishment from two years in prison to 10.

“There’s already strong self-censorship in Hong Kong in the past few years,” Lai said, pointing to the removal of politically sensitive books from public libraries and schools.

During last year’s Hong Kong Art Week, a video installation by an American artist was removed from a billboard outside a department store after it was discovered to be secretly paying tribute to the 2019 protesters, more than 10,000 of whom have been arrested.

In August, a longstanding mural was removed from outside a restaurant popular with construction workers because it depicted patrons eating noodles while wearing yellow hard hats, a color associated with pro-democracy protesters.

In recent months, national security considerations have also seemingly played a role in the cancellation of multiple performances. In January, organizers of the Hong Kong Drama Awards said they had been told that the government-funded Hong Kong Arts Development Council was withdrawing support for the first time in more than two decades out of concern for its reputation.

Among the reasons the council cited was the invitation of “non-theatrical people” as presenters at last year’s awards, including the controversial political cartoonist known as Zunzi.

Lai said the heightened legal risk brought by the Article 23 law would worsen self-censorship, which in turn would “make Hong Kong become less vibrant and pluralistic and further discourage artistic communities from abroad to visit Hong Kong.”

The effects of self-censorship could also ripple out from Hong Kong to the wider world, Wear said, noting that Western galleries and other arts organizations have rarely contended with restrictive laws of this kind in an art market as big as Hong Kong’s. Like Beijing’s national security law, the Article 23 law claims global jurisdiction.

“If you’re a dealer bringing work, say, to Art Basel, or if you have an operation in Hong Kong, you may hesitate about having work anywhere in your system that might upset the Hong Kong or Chinese authorities,” said Wear, who was associate head of the School of Design at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University from 1989 to 2006.

Galschiot said it was the responsibility of Western arts organizations and auction houses to speak out on behalf of a Hong Kong artistic community that has been “castrated” by the national security laws.

“They must take the fight now from the artists,” said Galschiot, whose sculpture was reportedly seized from storage by Hong Kong national security police last year in connection with an “incitement to subversion” case.

Hong Kong officials declined last year to confirm or deny reports that there was a warrant out for Galschiot’s arrest.

Wear said Hong Kong is unlikely to lose its prominent position in the art world any time soon.

“The art market is very likely to persist, and very possibly even likely to grow,” he said. “It’s just that a lot of things won’t be possible.”